How To Read The Bible Responsibly

Four Principles for Faithful Biblical Study

In our modern world of hot takes and quick opinions, approaching Scripture with care and responsibility has never been more important. The Bible remains the most influential texts in human history, yet it's often misunderstood, misquoted, and misapplied. How can we engage with these ancient texts in ways that honor their original context while still finding meaning for today? I'd like to offer four principles that have helped me navigate this sacred library with greater wisdom and humility.

1. Scripture Should Interpret Scripture

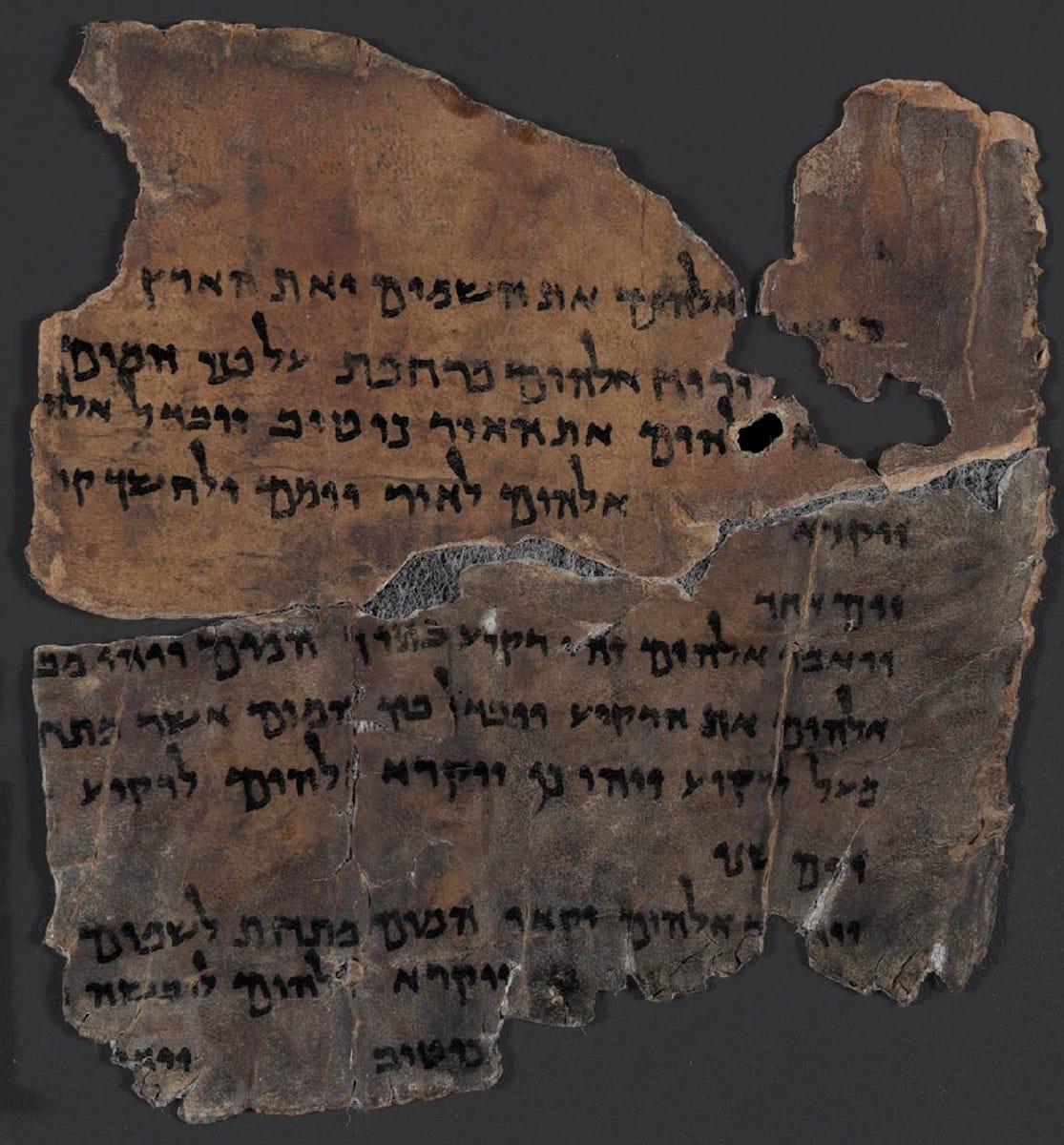

We've often thought of the Bible as a "book" but I think the more precise language is that the Bible is a "library of books." This means when we open up Scriptures, we actually have built into our Bible a library of books (66 books, 40+ authors, 3 languages, 2,000+ years) to help inform, clarify, and bring further direction. This means the first place we should go for answers to our questions about Scripture is Scripture!

This principle recognizes the Bible's in…